Kimberly Kopecky, M.D., MSCI, a UAB surgeon specializing in high-risk abdominal procedures, created The Empathy Project to help trainees improve at having tough conversations with patients and families.

Kimberly Kopecky, M.D., MSCI, a UAB surgeon specializing in high-risk abdominal procedures, created The Empathy Project to help trainees improve at having tough conversations with patients and families.

Have you ever met a doctor who could use some pointers in communication? Or a few lessons in empathy?

Nine years ago, Kimberly Kopecky, M.D., MSCI, was hoping to gain expertise in just those topics. During her surgery residency at Stanford University, she decided to pursue hospice and palliative medicine fellowship training. “I knew that I wanted to be able to have difficult conversations with patients and families and do it well,” she said.

A surgeon will have tens of thousands of these conversations over the course of a typical career. Kopecky’s goal was to be comfortable communicating difficult and sometimes devastating news. She matched to the fellowship program at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, both for its palliative care program and because of Margaret Schwarze, M.D., a vascular surgeon who is world-renowned for her research on doctor-patient communication and surgical decision-making. At the time, Kopecky, who is now an assistant professor in the UAB Division of Surgical Oncology specializing in high-risk abdominal procedures, was only the second surgeon to complete fellowship training in hospice and palliative medicine in the middle of surgical residency.

“Even when I was in my first year of surgical residency, I could tell that there were doctors who knew how to have difficult conversations and others who didn’t. But that doesn’t mean you are ‘born with it.’ It is a skill you can practice.”

As a palliative care fellow, Kopecky learned from experts and developed skills to guide and support patients and families through some of medicine’s most challenging moments. The more she learned, the more she wanted to grow — so she and another fellow, Jasmine Hudnall, D.O., designed a makeshift game as a way to practice.

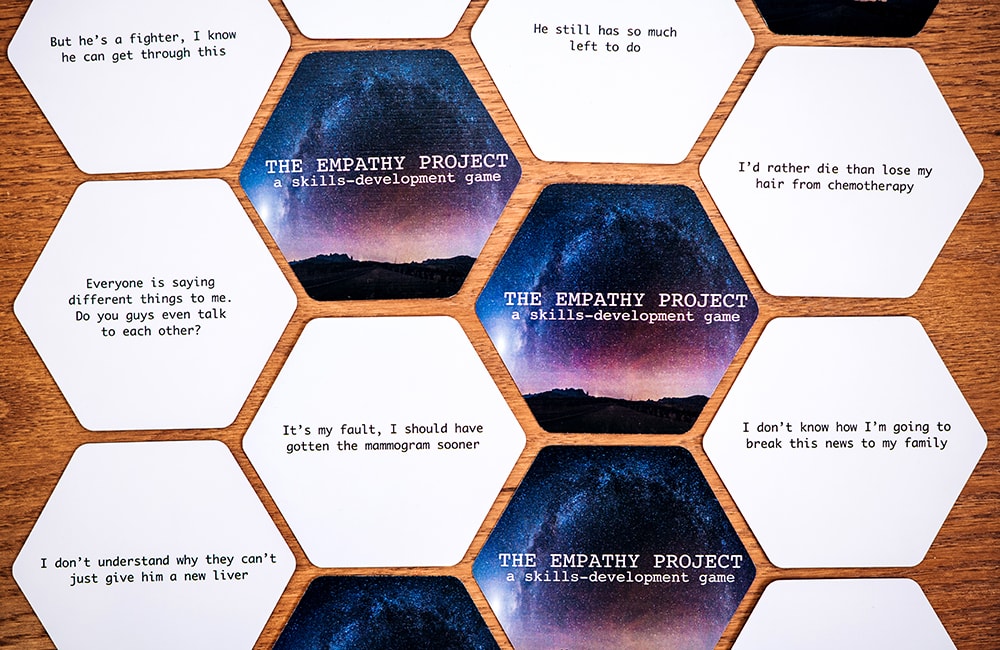

Talking it over in the fellows workroom, Kopecky and Hudnall took some sheets of paper and wrote out as many tough patient and family questions and statements as they could think of. “The goal of the game was to practice responding to these statements with empathy, instead of slipping into a ‘cognitive response,’” Kopecky recalled. They came up with rules: Each player gets a few minutes to write out an empathetic answer to the question, and then all participants discuss the best responses. The practice helped, so they tried the game out with their fellow trainees, then with residents. Eventually, their sheets of paper were so worn that they decided to get them professionally printed; The Empathy Project: A skills-development game is available online.

“Even when I was in my first year of surgical residency, I could tell that there were doctors who knew how to have difficult conversations and others who didn’t,” Kopecky said. “But that doesn’t mean you are ‘born with it.’ It is a skill you can practice.”

Why can’t you just give him a new liver?

Then, and now, Kopecky pictures this question coming from a middle-aged daughter who has been told that her elderly father, in the intensive care unit with acute liver failure, is dying.

“This daughter is not asking for information,” Kopecky said. “She doesn’t need an explanation of MELD scores or the qualifying criteria for a transplant. What she needs to hear is something like, ‘It must be so hard to see your father so sick.’ Recognizing and acknowledging the emotional drivers of patient and family questions, especially in the midst of critical or serious illness, is key to making them feel seen and heard. But unsurprisingly, the natural response of any medical or surgical trainee is ‘Let me explain to you why he can’t have a new liver.’”

In a new paper, Kopecky describes the cognitive trap as a situation in which providers interpret all patient and family questions as requests for factual information. “I tell our surgical residents, ‘When someone keeps on asking questions, that’s an indication that you haven’t actually responded to the underlying emotion driving that person’s question.’”

It is hard for surgeons to resist giving an answer like this, Kopecky says. She and her co-authors have coined a term to describe the problem: the cognitive trap. In a new paper, Kopecky describes the cognitive trap as a situation in which “healthcare providers rigidly interpret all patient and family questions or statements as requests for factual or technical information.” They continue: “We have seen in practice that when surgeons exclusively offer cognitive and information-focused answers in these moments it can lead to inadequate reassurance, and in some cases, increased patient or family distress despite otherwise excellent care.”

“We become surgeons because we like solving problems and having answers and making fixes,” Kopecky said. “And so much of a surgeon’s training is geared to making sure you know the right answer.”

Patients and families, like attending physicians, often have questions. Underneath those questions, however, are powerful emotions. “I tell our surgical residents, ‘When someone keeps on asking questions, that’s an indication that you haven’t actually responded to the underlying emotion driving that person’s question,’” Kopecky said.

But emotions can feel threatening, both to surgeons’ own well-being and to their notoriously packed schedules. “Many surgeons think, ‘If you ’get into the feelings,’ it is going to take 40 minutes and you are not going to be able to extract yourself,’” Kopecky said. “But I find that that is not true. If you can address the grief or fear or anxiety that is underneath the question, you often can actually avoid getting paged with follow-up questions all afternoon.” Or, as Kopecky and her co-authors write in their paper, “When patients and families feel heard, conversations are more focused, and visits may be shorter, further supporting the value of emotionally attuned responses in routine surgical care.”

Avoiding the trap

In their paper, Kopecky and colleagues note that avoiding the cognitive trap “requires two deliberate steps: identifying the emotional components of patient and family communication, and responding to those emotions before offering medical information.” The acronym NURSE summarizes different ways to respond with empathy, Kopecky says: Name the emotion, Understand, Respect, Support and Explore.

At UAB, Kopecky plays The Empathy Project game regularly with the residents she is training. Even though they know the purpose of the exercise, most of these young doctors still write fact-based, overly explanatory answers on the first round, and the second. “Usually by round three, they have cut back the number of words they are using to respond, and started to realize, as a group, how easy it is to drop into technical speak and slip under the question,” Kopecky said. “We’re not trying to coach people to have a stock answer when they get a question. But we know that structured practice can help anyone to improve their communication skills.”

Part of a new curriculum for communication in surgery

After she completed her palliative care fellowship at the University of Wisconsin, including working on doctor-patient communication research with Schwarze, Kopecky finished her surgical residency at Stanford, then completed a second fellowship in surgical oncology at Johns Hopkins. Over the years, Schwarze and Kopecky stayed in touch; when Schwarze began developing a curriculum known as Fundamentals of Communication in Surgery, she asked Kopecky to join the effort. The curriculum is being tested across a diverse group of general surgery residency programs nationwide. The Empathy Project card game is a part of that curriculum.

“Our goal is to make it so that you don’t need fellowship training to be able to learn important communication skills,” Kopecky said. “Just as we teach trainees surgical skills, we can also teach them communication skills.”

Understanding expectations

Kopecky specializes in a procedure called cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC (hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy). This complex operation, which can last anywhere from 12 to 16 hours or more, is a treatment for stage IV appendix, colorectal, peritoneal mesothelioma and gastric cancers. Kopecky is the only surgeon in Alabama performing the procedure (watch her discuss the surgery in this video).

With an internal grant from UAB’s Center for Palliative and Supportive Care, Kopecky has been interviewing patients and families about what they expect life after surgery to be like. “In palliative medicine, we think a lot about reducing pain and suffering,” Kopecky said. “One of the main sources of suffering is a mismatch between the experience of what you think it is going to be like and what it is actually like. My hypothesis is that, if you can better align expectations before surgery with the realities of surgical recovery and life after surgery, then perhaps we will be able to move the needle to reduce suffering in patients undergoing surgery for cancer.”

Kopecky has also released a national survey of patients who are considering or have undergone cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC. “The purpose of the survey is to better understand what patients wish they had known going into the surgery, with the goal of generating nationally distributable pre-operative patient and caregiver information materials that capture the patient experience,” Kopecky said. “We want to make patient-informed materials that collect these stories, to help future patients learn and benefit from the experience of patients who have come before them.”