Starting a new medicine is as simple as taking your prescription to the pharmacy. But how do you know when it is time to quit taking a drug altogether?

Starting a new medicine is as simple as taking your prescription to the pharmacy. But how do you know when it is time to quit taking a drug altogether?

That question turns out to be highly complex and increasingly relevant as the population ages. More than half of Americans age 65 or older are taking four or more prescription medications; 12 percent are taking at least 10 medications. The trend is accelerating. Three times as many older adults today are taking five medicines or more compared with 20 years ago.

These drugs can be critical for preserving health, of course. But there can be potentially dangerous interactions among them. And there is another complicating factor: As we age, physical and chemical changes mean that the same dosages that were once just right may not work the same way they once did.

“Certain conditions are overtreated in older patients,” said Kenneth Boockvar, M.D., director of UAB’s Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics and Palliative Care. Geriatricians have a primary mission “to protect people from harm, and medicines are part of that,” Boockvar explained. “My biggest goal lately has been how to bring deprescribing into routine visits and culture — to ask, ‘What can we treat?’ but also, ‘What do we need to no longer treat?’ I think we are getting there. Multiple professional societies have added deprescribing guidelines lately.”

“My biggest goal lately has been how to bring deprescribing into routine visits and culture — to ask, ‘What can we treat?’ but also, ‘What do we need to no longer treat?’" said Kenneth Boockvar, M.D., Ph.D., director of UAB’s Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics and Palliative Care.Deprescribing, both the idea and the word, “arose not long ago to refer to reducing the potential harm from medicines,” Boockvar said. “That includes older adults, but it could be anybody; young children are also vulnerable because they are smaller.”

“My biggest goal lately has been how to bring deprescribing into routine visits and culture — to ask, ‘What can we treat?’ but also, ‘What do we need to no longer treat?’" said Kenneth Boockvar, M.D., Ph.D., director of UAB’s Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics and Palliative Care.Deprescribing, both the idea and the word, “arose not long ago to refer to reducing the potential harm from medicines,” Boockvar said. “That includes older adults, but it could be anybody; young children are also vulnerable because they are smaller.”

Scenarios in which deprescribing might be appropriate, Boockvar says, include when

- medications are inconsistent with patients’ health care goals, or “what matters most” — goals that may change as patients get older or more frail;

- more than one medication is being taken for the same thing (duplication); and

- medications are having adverse effects on cognition and physical function.

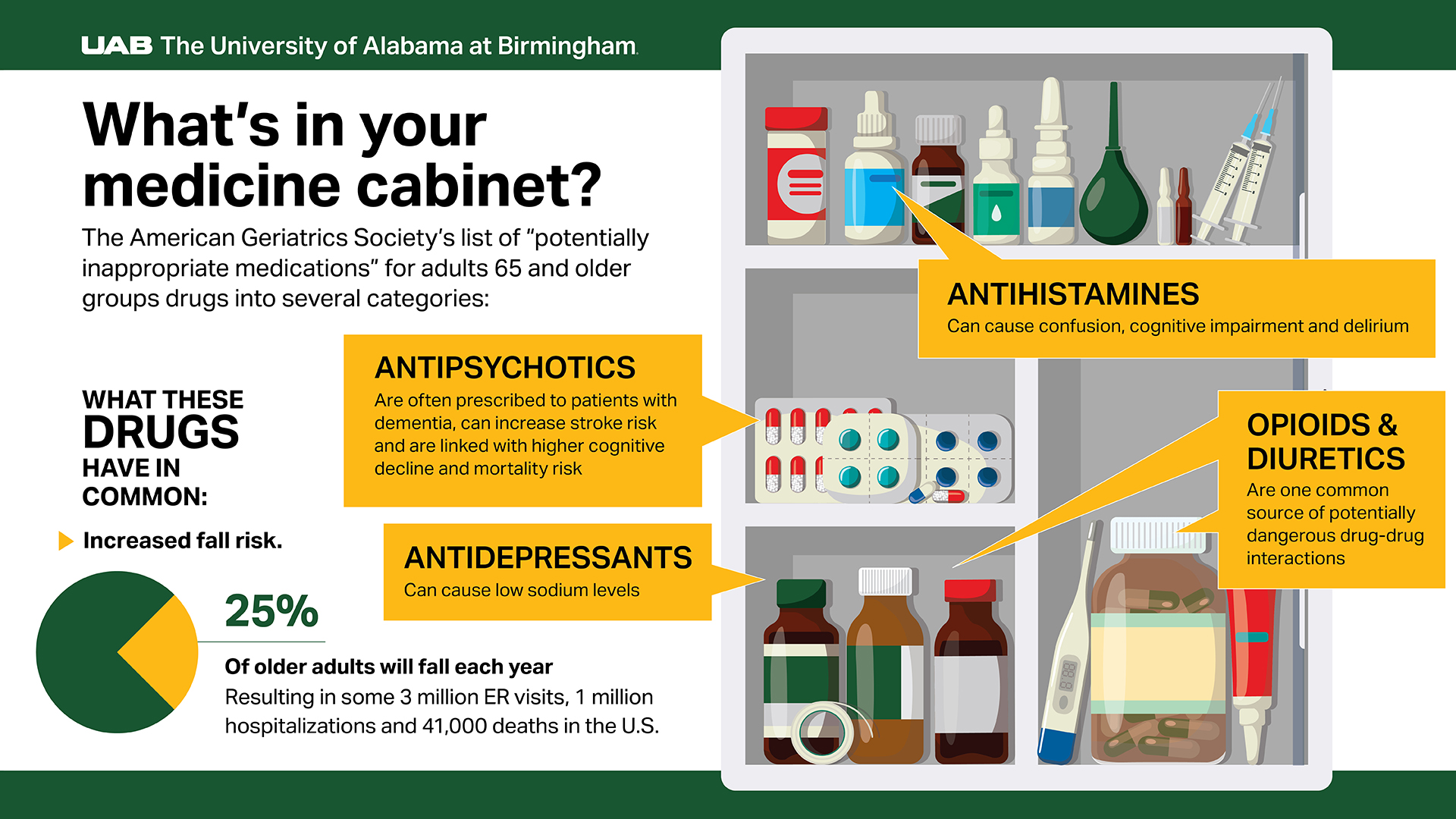

Since 2011, the American Geriatrics Society has published a list of “potentially inappropriate medications” for adults 65 years old or older. The list, updated every four years, groups drugs into several categories:

- medications that are potentially inappropriate, such as antihistamines, which can cause confusion and an increased risk of falls;

- antipsychotics, often prescribed to patients with dementia, which bring an increased risk of stroke and greater rates of cognitive decline and mortality;

- antidepressants such as the widely prescribed SNRIs and SSRIs, which can cause low sodium levels; and

- potentially clinically important drug-drug interactions, including opioids, antipsychotics and diuretics.

A common thread is the increased fall risk that many medications bring for older adults. And the results of a fall in seniors can be life-altering. The rate of deaths from falls in older adults is increasing over time, rising by 41 percent between 2012 and 2021. Each year, a quarter of older adults will fall, and falls result in approximately 3 million emergency room visits, 1 million hospitalizations and 41,000 deaths in the United States, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Boockvar leads a falls clinic at the Birmingham VA Health Care System, and “deprescribing is a big part of our VA Falls Clinic,” he said.

Boockvar directs UAB’s Integrative Center for Aging Research. The center’s mission is to promote the health and well-being of older adults and their families through research, education and outreach initiatives. “As a geriatrician, I would see my patients struggle with some medications, including side effects that would affect their thinking and mobility,” Boockvar said. “That got me interested in managing medicines and the side effects of medicines. I also developed an interest in figuring out what patients were taking and the process of ‘medication reconciliation,’ which is when a member of the health care team takes a thorough medication history and compares it to what is recorded in the health care record.”

Graphic points out several types of medications that are potentially inappropriate for adults 65 and older. See a full text-only version of this graphic below.

Graphic points out several types of medications that are potentially inappropriate for adults 65 and older. See a full text-only version of this graphic below.

What’s in your medicine cabinet?

This last question, Boockvar says, is not as easy to answer as it seems. “You would think there would be a true medicine list somewhere, where someone has written down everything we know about a patient,” Boockvar said. There is not, in the fragmented American health system, and even the most direct route to building one — asking patients — is not guaranteed to work. “A patient might say, ‘Yes, I’m taking this,’ but the reality is that they are taking it incompletely. And then the other part is that medicines are constantly changing. You may have a true medicine list the day you see a patient, but the next day they see another physician and they get a new prescription.”

Today, Boockvar and colleagues call it a “best possible medication history,” which has its own medical abbreviation, BPMH. This is “acknowledging how hard it is to pin this down,” he said. He also points out that this history includes more than prescriptions. It is also important to know about over-the-counter medicines, supplements and home remedies that patients are taking as well, Boockvar says. Doctors also ask about marijuana and THC-containing products, because these can interact with prescription medicines, too, he adds.

Simply identifying an unnecessary or unhelpful treatment is not enough, Boockvar says. The next challenge is to convince the patient and/or their caregivers to make a change.

“‘Deprescribing’ as a term is a little fraught,” Boockvar said. When they hear the word, “some people think you are taking away medicines they deserve, that they should want to take.”

His own experience, and research, suggest that, “if you are going to make a change, especially if you are going to suggest that a patient doesn’t need a medicine anymore, you have to approach that carefully,” Boockvar said. “They may have been told, ‘You need this the rest of your life,’ and now you are telling them something new. Instead, you might say, ‘Aggressive control of your diabetes is not as important now that you are 90; what matters most to you is avoiding episodes of low blood sugar and how that makes you feel. This drug is probably risky.’”

Boockvar is leading a grant from the Birmingham VA Medical Center supporting several research projects around the country.

- A Boston-based study focused on diabetes is sending educational information in the mail to patients taking high-risk medications, encouraging them to talk with their doctors. “They are seeing that patients bring these brochures in to their doctor, and that results in a conversation about deprescribing,” Boockvar said.

- A similar effort at the Birmingham VA is focusing on rheumatology patients, led by UAB rheumatologist and Principal Investigator Maria Danila, M.D. “People with joint diseases are often on pain medicines and also anti-inflammatory drugs known as corticosteroids,” he said. “That combination is risky.” The pilot project is focusing on patients who are taking both drugs, encouraging them to reduce dosages and lower the risk of adverse effects.

- In Durham, North Carolina, researchers are talking about deprescribing with caregivers. “A lot of our older patients unfortunately have cognitive issues, and they have high risk for worsening cognition,” Boockvar said. “Often, we are talking with caregivers; they are piloting an intervention in which the audience is the caregiver.”

- Boockvar is participating in another study, based in New York City and Boston, focused on identifying patient medications during telemedicine home visits “to develop a best possible list of medicines to make recommendations,” he said.

At UAB, “we are growing a critical mass of researchers” interested in deprescribing, Boockvar added. At the School of Nursing, Professor Rita Jablonski, Ph.D., recently led an effort to call prescribers at nursing homes in the area to talk with them about the potential harms of antipsychotic medicines. “These are particularly strong medicines that are used to calm folks with dementia, and they are sometimes overused,” Boockvar said. Rachel Skains, M.D., MSPH, assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine, is comparing the effectiveness of different deprescribing initiatives in emergency departments nationwide. Helen Omuya, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Health Services Administration in the School of Health Professions, is studying pharmacist-based deprescribing interventions.

“Understanding patients’ health care goals and optimizing medications are also two pillars of UAB Medicine’s ‘Age-Friendly’ health care transformation, led by Dr. Mark Newbrough in the Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, and Emily Simmons, MSN, R.N., CNL, in UAB’s Department of Interprofessional Practice and Training,” Boockvar added.

Looking ahead, Boockvar says, UAB and other researchers are interested in using artificial intelligence to review patient records and make recommendations for medicines that may no longer be needed.

Story continues after box

Why do medicines affect older adults differently?

As people grow older, multiple changes combine to alter how their bodies react to drugs:

- Average heart rate drops

- Baroreceptors (stretch sensors) in major arteries do not expand as they once did, leading to lower blood pressure

- Kidney filters do not work as well

- Liver filters do not work as well

- Sodium retention is impaired

- Epinephrine response decreases

- Increased receptor sensitivity to some drugs, including benzodiazepines and opioids, and decreased sensitivity to beta blockers, among others

As people grow older, the heart does not pump as much blood as it once did. And the baroreceptors, stretch sensors in the main arteries, become less effective at making fine-tuned adjustments to heart rate and blood vessel tension. These combine to make older adults more prone to orthostatic hypotension — a drop in blood pressure when standing up. That means that a formerly effective dose of a blood pressure drug can leave elderly patients on the borderline of low blood pressure.

Another chronic condition that changes with age is Type 2 diabetes. Each year past age 40, the kidneys lose some of their ability to filter the blood, meaning that medications are not cleared out of the body as fast as they once were, increasing the risk of low blood sugar or hypoglycemia. Another issue: Epinephrine response decreases with age, and epinephrine causes the warning symptoms of hypoglycemia, including feeling hungry, shaky and/or sweaty.

What will happen when you stop?

Even if Boockvar could get a completely accurate list of medicines, more research needs to be done to untangle the complex web of potential interactions among them, he says.

“Interventions to reduce medicines are effective at reducing medicines,” Boockvar said. “Our challenge is to show that the patient feels better or is moving better or having less side effects when they stop taking a medicine … or at least that their health is the same.”

This is important because “showing that health is the same without a medicine as with a medicine means ‘why take a medicine if there isn’t a difference?’” Boockvar said. “We can save the patient hassle and the patient and the system the cost, and if the medicine is not making any difference, it should come off.”

Graphic: What's in your medicine cabinet?

The American Geriatrics Society's list of "potentially inappropriate medications" for adults 65 and older groups drugs into several categories.

What these drugs have in common:

- Increased fall risk

25% of older adults will fall each year, resulting in some 3 million ER visits, 1 million hospitalizations and 41,000 deaths in the U.S.

Categories of potentially inappropriate medications:

Antipsychotics

- Are often prescribed to patients with dementia

- Can increase stroke risk

- Are linked with higher cognitive decline and mortality risk

Antihistamines

- Can cause confusion, cognitive impairment and delirium

Antidepressants

- Can cause low sodium levels

Opioids and diuretics

- Are one common source of potentially dangerous drug-drug interactions

Information provided by The University of Alabama at Birmingham