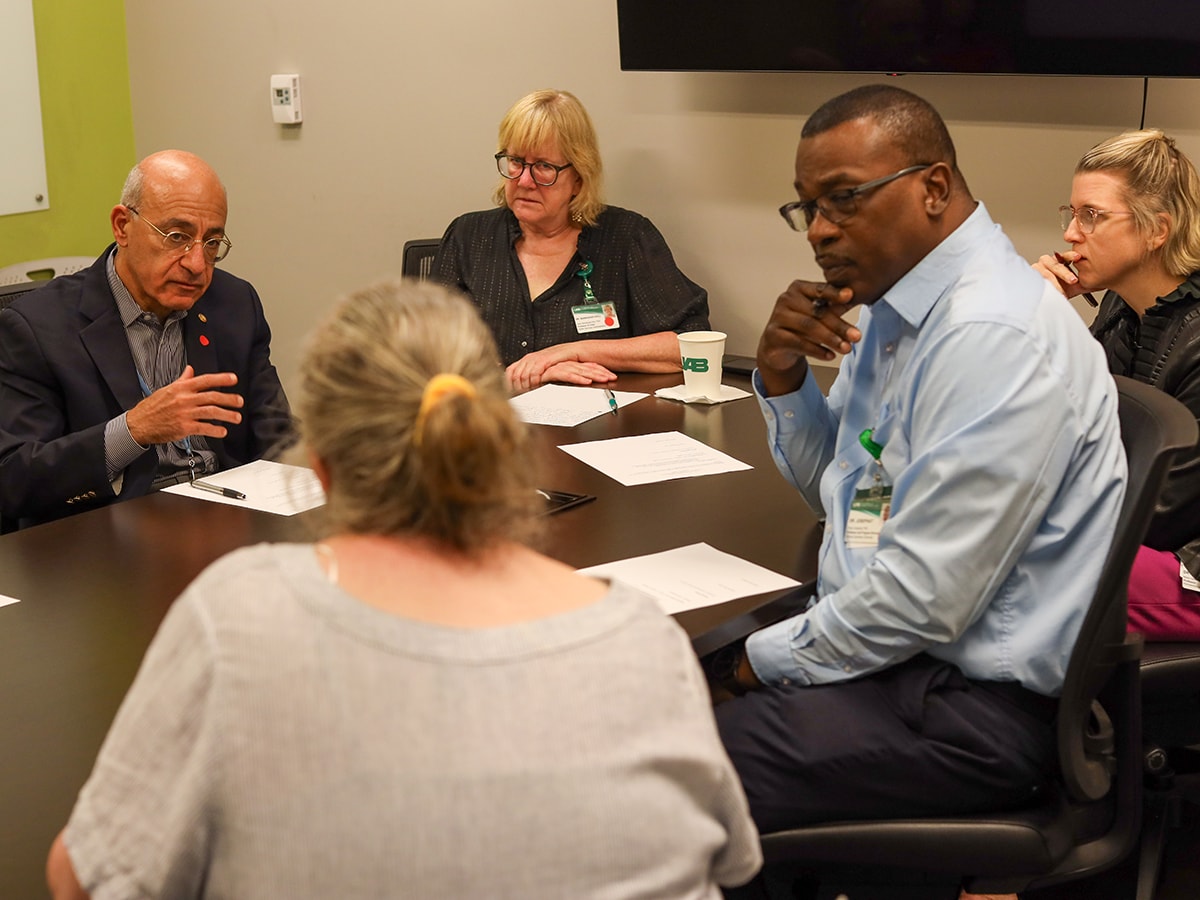

This summer, department chairs at their annual retreat faced scenarios drawn from real HR cases: a staff member reporting burnout, a faculty request for costly travel accommodations, an employee who might pose a safety risk.

The exercise let chairs see how their peers handle similar situations, get feedback on their own decisions and affect, and share strategies for defusing tense moments.

“Your heart is beating faster”

“None of us knew ahead of time what the case would be like,” said Yuliang Zheng, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Computer Science in the College of Arts and Sciences. “Ours was something that I have had to deal with many times as an experienced chair, but even then there is always something new with each incident. And even though you know it is a simulation, it feels so real. My heart was beating faster.”

That was the idea. UAB’s health programs have long used simulated patients or simulated participants (SPs) to prepare students for the nuances of patient encounters. Having practice with this skill makes a big difference when a student has to make their first difficult diagnosis or respond appropriately to a distraught family member. Could the same approach help academic leaders?

At a pre-semester retreat in August, the UAB Center for Interprofessional Education and Simulation (CIPES) put that question to the test. The unique training they developed gave dozens of academic chairs and assistant deans a chance to practice active listening and resource referral in a safe setting.

Simulation is “even more helpful than we had imagined”

When a recent reorganization put CIPES under Michelle Robinson, DMD, MA, senior vice provost for Faculty and Academic Affairs, she wanted to showcase its potential beyond health care. “We want to increase our profile on campus,” Robinson said. “Many of our faculty in the health schools know how useful simulation can be, but this retreat and the reception from participants showed us it is even more helpful than we had imagined. There are so many ways to use simulation. This was proof that the sim center can be used in this way.”

Robinson recalls an incident from her time in the School of Dentistry, when she was charged with leading an initiative to implement a new electronic records system that had significant pushback from trainees. “I was in a meeting and someone stood up and yelled, ‘I’m not going to do this and you can’t make me,’” Robinson said. “I think if I had had a chance to practice something like that before, I would have felt much more prepared to handle that situation.”

Dawn Taylor Peterson, Ph.D., director of the Office of Interprofessional Simulation, developed the simulation cases with her team and in collaboration with Shawn Galin, Ph.D., director of the Office of Standardized Patient Education, and Allison Shorten, Ph.D., director of the Office of Interprofessional Curriculum. (The three offices together make up CIPES.) “The main learning objective was to practice active listening and point employees to the most appropriate resources on campus,” Peterson said. “We worked with Human Resources to identify common, challenging cases — two involving faculty and two involving staff — and worked with staff from UAB’s Employee Assistance and Counseling Center and AWARE Disability Management Program to develop the scenarios and appropriate responses.”

Eugene O’Neill in a conference room

The retreat was a hit. “The response has been really wonderful,” Robinson said. “Multiple academic leaders have asked me if we are going to do it again so they can take part, and we have had discussions with several groups who want us to do something similar for their employees. And now the team is putting together a presentation for a national conference about the experience. We have had discussions about doing research involving simulation and AI as well. It is really interesting for every one of our missions: research, education, practice and service.”

This was the first time that Patrick Evans, D.M., chair of the Department of Music, was part of a simulation. His scenario involved a new employee requesting to leave early twice a week because of a mixup in daycare scheduling, despite being the sole front-desk staffer until 5 p.m. “It was not someone who had been there for years and built up a lot of trust,” Evans said. “But the HR rules need to apply fairly and evenly, so what do you do?” The SP portraying the role of the employee “was really quite good and she was able to cry when recounting her story,” Evans said. “It was like watching a Eugene O’Neill play in a conference room.”

His group found a way to accommodate the request, but the bigger lesson came during reflection. “We realized how long we left her waiting outside while we deliberated,” Evans said. “Next time, I’ll minimize that. Waiting after making yourself vulnerable is nerve-wracking.”

Simulations “can do so many things”

Evans, a chair for more than a decade, said the exercise was both practical and energizing. “Some scenarios I’d faced before, others I wouldn’t have known what to do,” he said. “It was helpful and a great way to connect with colleagues. It helped me roll up my sleeves for the new semester and feel like there are other people across campus doing the same thing.”

“As a chair, active listening, problem solving and having difficult conversations are all challenging parts of the job,” said Mia L. Geisinger, DDS, MS, professor and acting chair of the Department of Periodontology in the School of Dentistry. “We want to make sure that we are compliant with UAB policies and still take a humanistic approach to our colleagues within the department. The simulation was an excellent way to practice communication skills and active listening to distill a distressed employee’s concerns.”

“The scenario was very realistic to what we deal with as chairs on a daily basis,” said Curry Bordelon, DNP, MBA, CRNP, interim chair of the Department of Family, Community and Health Systems in the School of Nursing. “But because we were there with seven or eight other chairs and assistant deans from all over campus, it provided us with an opportunity to think about how else we could approach these situations. It is very common to have to think on your feet about requests from faculty and staff — this was a helpful opportunity for developing that skillset.”

One of his biggest takeaways, Bordelon added, “is that the sky is the limit with simulation.” As a neonatal nurse practitioner with 25 years of experience, “I have done a lot of transition-to-practice simulations with students and leadership simulations in our doctor of nursing practice program,” he said. “Simulations can do so many things. The point is never to trip people up or confuse them, but to build people up.”