In. Out.

In. Out.

You have been breathing your whole life without thinking about it. But imagine if a machine — a mechanical ventilator — muscled its way into that delicate, unconscious dance. It is trying to help, but its algorithms cannot handle every tricky situation. Like when your brain senses it is suffocating and tries to take over.

Ventilators are a mainstay of any intensive care unit. When TV doctors talk about taking a patient off life support, it is often the ventilator that they mean. More than a million Americans are placed on ventilators each year. In busy, high-acuity ICUs such as those at UAB, 40 percent or more of patients may be attached to one.

Real ICU doctors, called intensivists, know that ventilators are both incredibly useful and a real danger.

Many patients hate being on them. A UAB clinician interviewed during the COVID pandemic illustrated one reason. Compared to a normal breath, he said, getting oxygen from a ventilator can be like “standing in front of a leaf blower.”

In. In. Ou. I… Ouuut. In! In!!!! I Can’t Breathe!

An improperly synchronized ventilator might give a breath before a patient is ready. Or it might not detect the patient’s attempts to breathe at all. This gives the patient a terrifying feeling of suffocation called “air hunger.” Today’s ventilators are very smart, but the variables are staggering. One journal article lists dozens of factors that can lead to a breathing mismatch known as patient-ventilator dyssynchrony, including the patient's medications, pain or agitation, stress, and muscle weakness from their illness. These factors can shift from hour to hour, meaning that ventilators must be watched carefully. Patient-ventilator dyssynchrony is a major reason that many patients on ventilators must be heavily sedated, even though this slows their progress in healing.

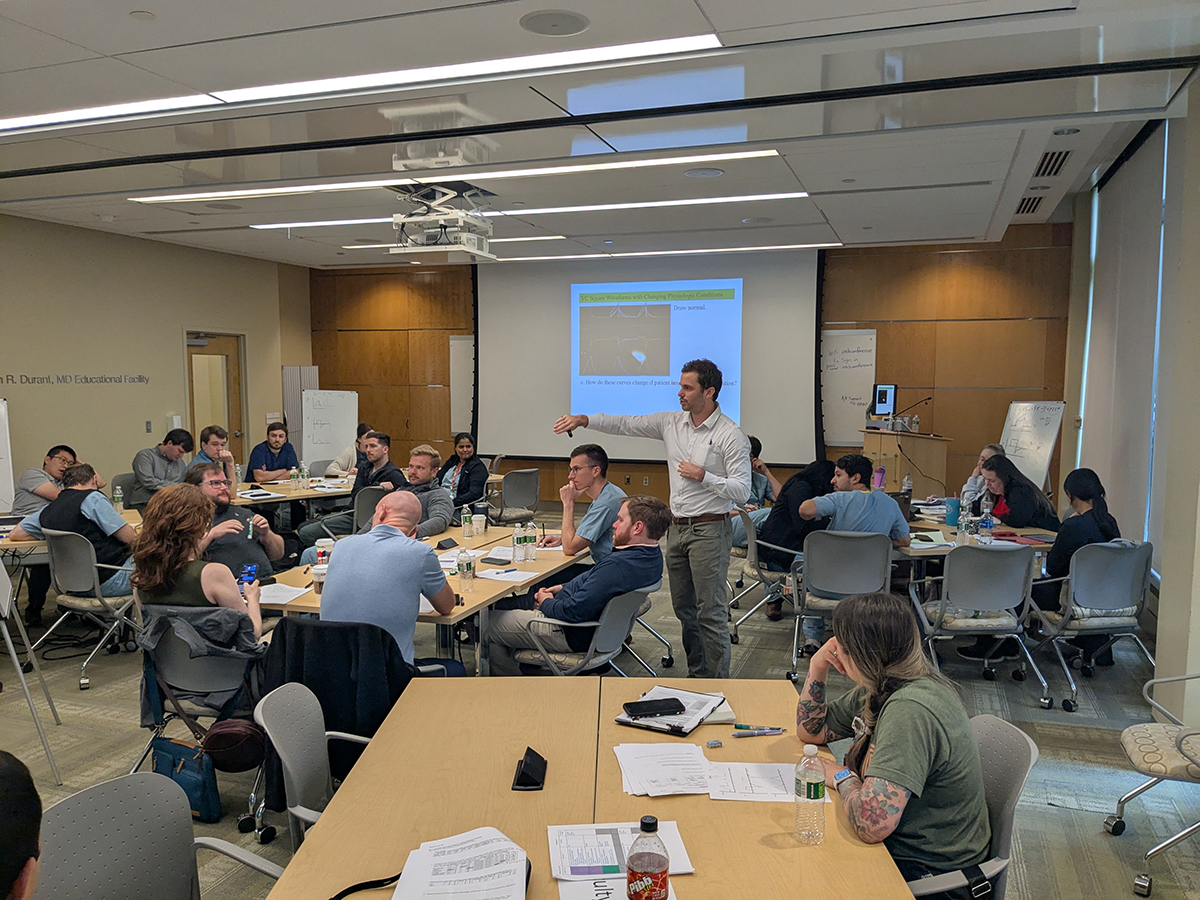

At the first Multi-institutional Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course at UAB, held in summer 2025, 26 participants, including trainees and faculty, learned to understand ventilators at a deep level.

At the first Multi-institutional Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course at UAB, held in summer 2025, 26 participants, including trainees and faculty, learned to understand ventilators at a deep level.

“A necessary evil”

“Ventilators are a necessary evil,” said Abdulhakim Tlimat, M.D., instructor in the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine in the UAB Heersink School of Medicine. “If you are in respiratory failure, you have to be on the ventilator; but there is a tradeoff.”

Some of the signs of trouble are obvious. Many are so subtle they are often missed. “Anybody who is on a ventilator could have an issue with the ventilator,” said Jonathan Kalehoff, M.D., an assistant professor in the division.

“When I went into my fellowship, I thought I would become an expert at managing mechanical ventilators,” Kalehoff said. “I learned how to troubleshoot the ventilator, but not to really understand it. I knew there was more I could do for my patients if I grasped what the ventilator is doing at a deeper level.”

A few years ago, Kalehoff found what he was looking for at a continuing medical education conference in Thailand. He was there acting as an academic assistant to Burton Lee, M.D., whom he had met through a shared interest in medical missions. But this was the first time Kalehoff had heard Lee unpack the hidden world of ventilators.

When Lee was a resident and fellow at Harvard Medical School, he had trained with many of the experts who wrote the textbooks on ventilators. Their understanding of ventilator mechanics and the equations that govern assisted breathing could make a major difference in patient care if it were widely shared, Lee realized. Later, at the University of Pittsburgh, he developed a hands-on course to do that. Word spread to medical schools around the Northeast; eventually, Lee joined the National Institutes of Health, and one of his mandates was to take his curriculum, now known as the Multi-institutional Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course, across the country and around the world.

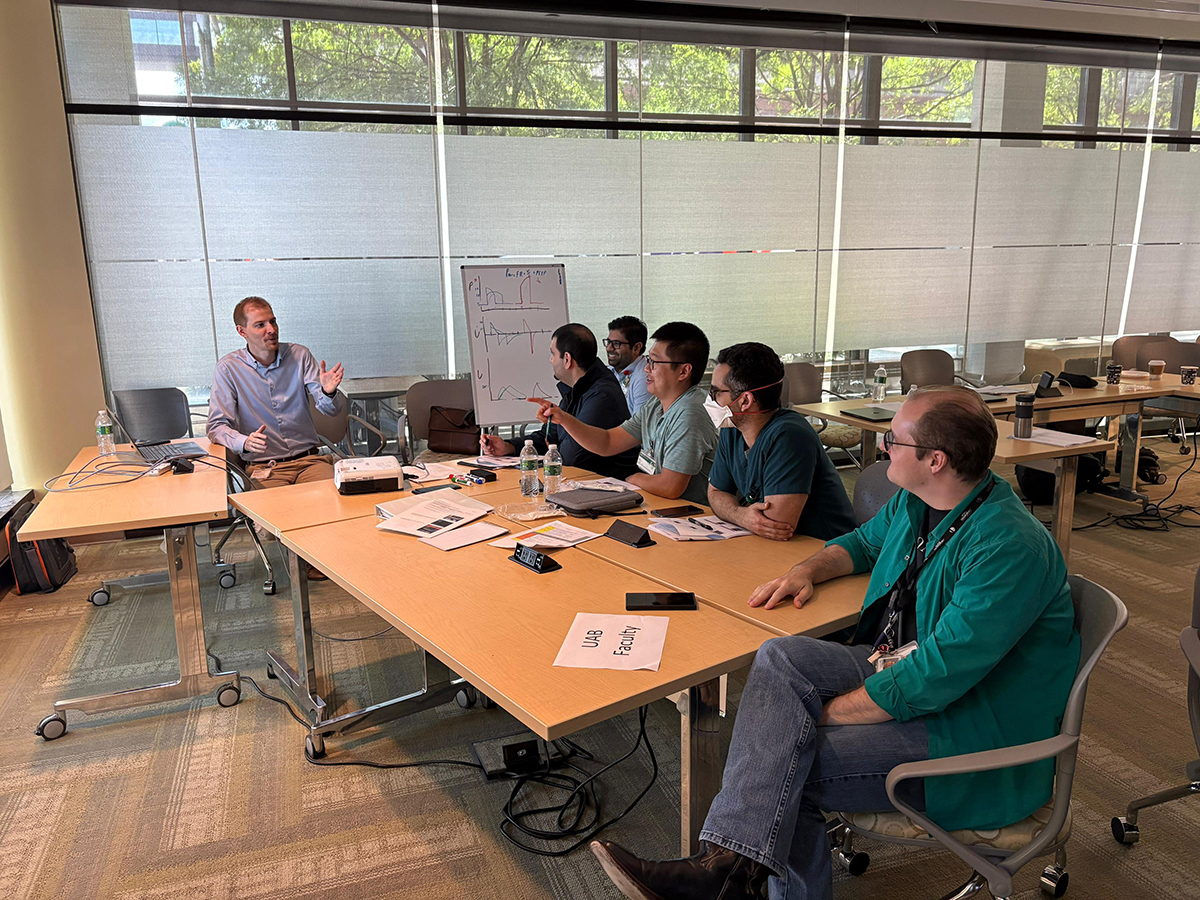

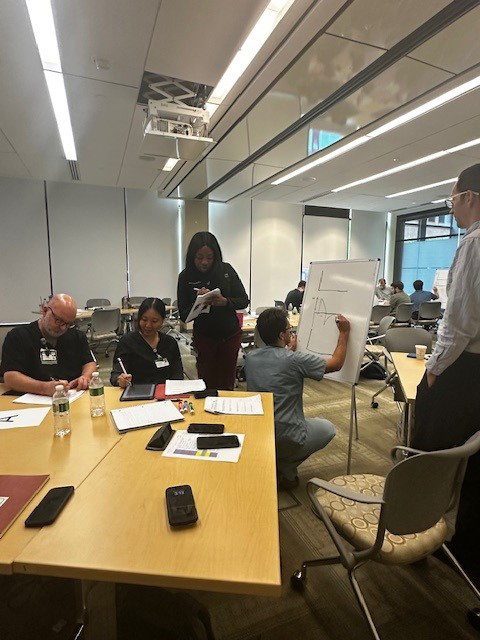

Jonathan Kalehoff, M.D. (left), interacts with faculty participants in the Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course. When Kalehoff first took the course himself in 2023, he and learners from leading institutions across the country had the same reaction: "I've never understood the ventilator like this before."

Jonathan Kalehoff, M.D. (left), interacts with faculty participants in the Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course. When Kalehoff first took the course himself in 2023, he and learners from leading institutions across the country had the same reaction: "I've never understood the ventilator like this before."

“I’ve never understood the ventilator like this before”

In 2023, Kalehoff took the full four-day Multi-institutional Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course in Washington, D.C. “There were learners from many leading institutions,” he said. “They all were saying, ‘I’ve never understood the ventilator like this before.’”

Kalehoff spent the next year taking a preceptorial course to expand his understanding and prepare to become a trainer himself. He also encouraged his colleagues to take the course so that they could bring it to UAB. Tlimat and assistant professors Steven Fox, M.D., and Daniel Scullin, M.D., took it in 2024 in Baltimore.

Kalehoff spent the next year taking a preceptorial course to expand his understanding and prepare to become a trainer himself. He also encouraged his colleagues to take the course so that they could bring it to UAB. Tlimat and assistant professors Steven Fox, M.D., and Daniel Scullin, M.D., took it in 2024 in Baltimore.

“What we have found is that, if you are expert enough, you can adjust the ventilator to give the patient what they want, instead of having them fighting the ventilator,” Kalehoff said. “That means less sedation. I can’t prove this yet, but I suspect that the people who have been through this curriculum are able to get their patients off ventilators a day or two sooner in many cases. And that translates into improved outcomes for patients, more capacity in our ICUs and lower costs.”

This summer, Kalehoff organized the first Multi-institutional Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course at UAB, with 26 participants — all of the trainees in UAB’s fellowship programs in Pulmonary/Critical Care, Critical Care Medicine, and Anesthesiology Critical Care Medicine, plus several faculty. Kalehoff, Tlimat, Fox and Scullin led the course in partnership with three guest faculty: Souvik Chatterjee, M.D., from Johns Hopkins University, and Emil Oweis, M.D., and Eric Kriner from MedStar Health.

“Fellows do a lot of the work in the hospital, with the attending physicians supervising,” Kalehoff said. “To make it possible for all the fellows to attend this training, attendings needed to cover all that the fellows do for those four days. Our division leaders made that happen; their support has been amazing.”

“We are always looking for ways to improve our fellows’ understanding,” said Tracy Luckhardt, M.D., professor and interim director of the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine. “Jonathan was very excited about the way this curriculum was taught .... When we had the opportunity to bring this training to the fellows, we wanted to make that happen. We went to the faculty and said, ‘We think this is really important. Can we figure out a way to cover for them?’ And our faculty were all behind that.”

UAB is now set to become a hub to spread this expertise throughout the Southeast, Luckhardt says. UAB is one of only 14 such hubs worldwide. UAB has also joined the Critical Care Education and Research Consortium, or CCERC, led by Lee, which tests and spreads new training programs for critical care specialists.

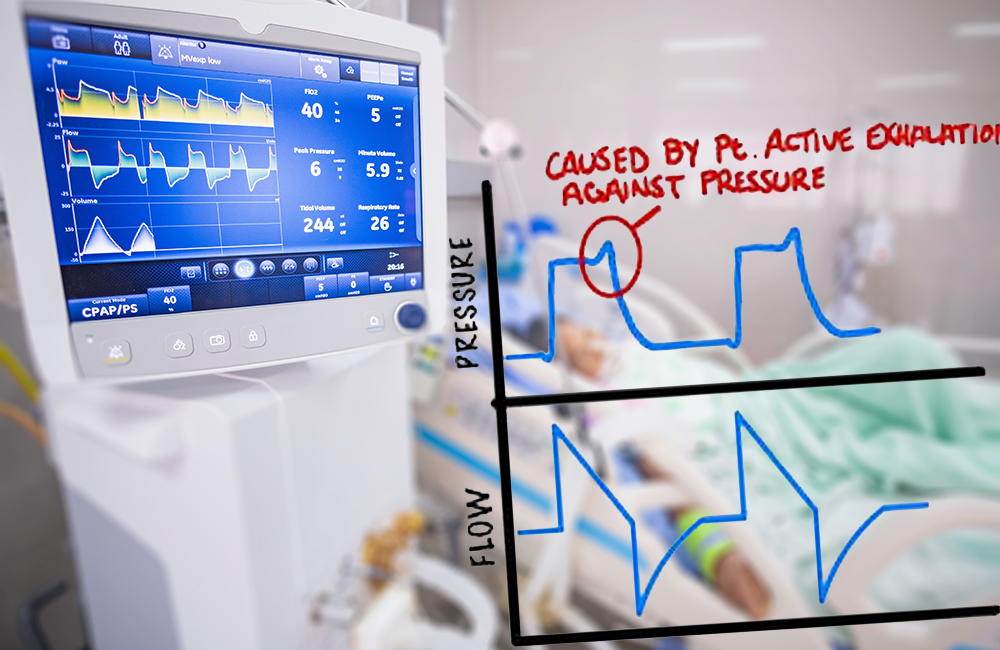

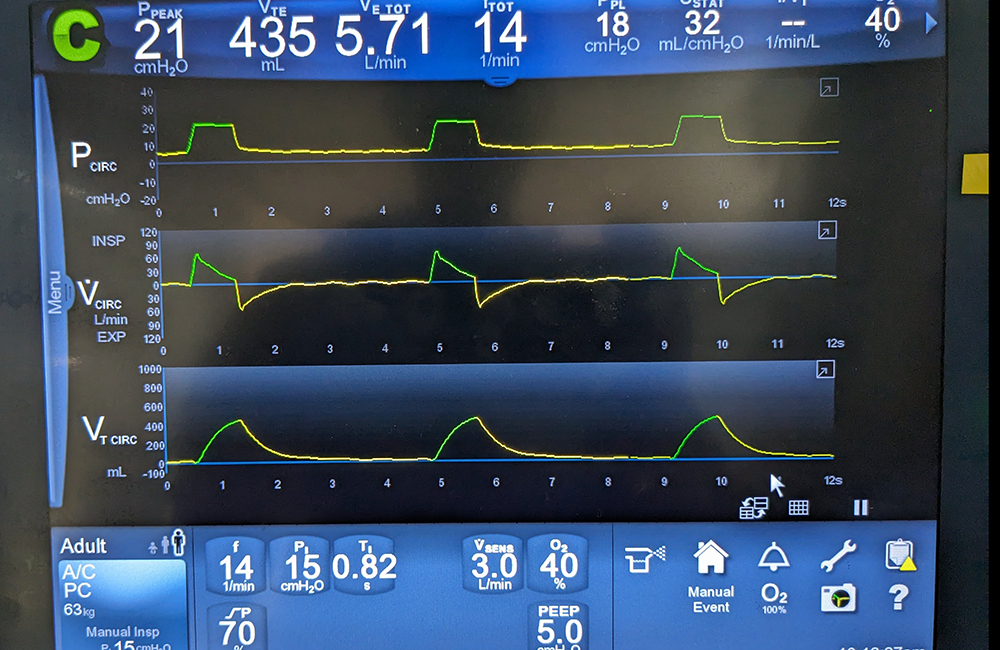

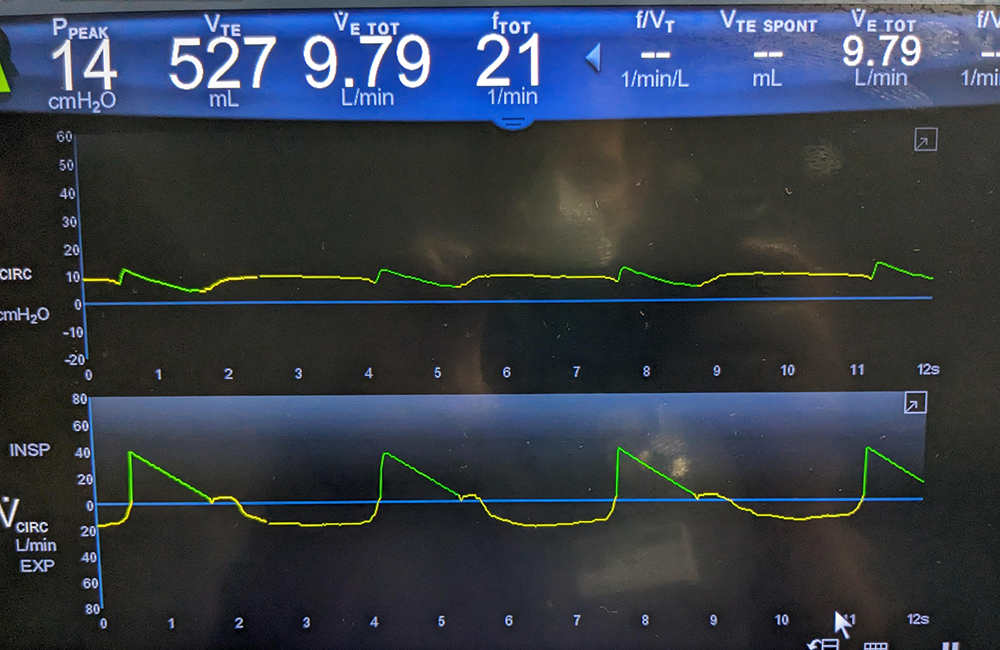

A ventilated patient displays normal waveforms in the image above. In the image below, a patient is experiencing severe flow starvation.

A ventilated patient displays normal waveforms in the image above. In the image below, a patient is experiencing severe flow starvation.

Training for the most difficult situations

An ICU doctor looking at a ventilator sees a scrolling series of waveforms charting second-by-second changes in air pressure, flow and volume.

“You can’t really understand what those lines are showing if you don’t understand the math and principles behind them,” Kalehoff said. Lee’s course teaches learners how to translate these waveforms into a mental picture of what is going on in the patient’s lungs. “What would happen if a patient’s airway started to tighten?” Kalehoff said. “When you know the principles, you know that should show up on the waveform as a swoop up. Just by looking at the waveform, you know what the patient is doing and how to fix the problem.”

“It is extremely valuable in helping you understand the mechanics of breathing and ventilation to a really deep level,” Tlimat said.

“Once you intubate someone, you have the onus on you to not mess it up,” said Fox, who trained at the University of Pittsburgh with Burton Lee before coming to UAB. “I firmly believe that the things we are doing in this course have an impact for our patients, and then an ongoing impact because our fellowship trainees will continue these practices wherever they go.”

Course participants practice drawing waveforms on a whiteboard.“Most doctors can solve an estimated 85 to 90 percent of the ventilator problems they will encounter,” Kalehoff said. “But what about that last 10 to 15 percent of people? This curriculum can help you respond in those situations.”

Course participants practice drawing waveforms on a whiteboard.“Most doctors can solve an estimated 85 to 90 percent of the ventilator problems they will encounter,” Kalehoff said. “But what about that last 10 to 15 percent of people? This curriculum can help you respond in those situations.”

How do you know it works?

Quantifying the value of new training is always a challenge. At the NIH, Lee started the CCERC to gather data on a much larger scale.

A 2020 paper by Lee and colleagues shared the impact of the Multi-institutional Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course. Between 2016 and 2019, 93 fellows from 10 fellowship programs were tested on their ability to recognize ventilator waveform abnormalities.

At the beginning of their fellowships, trainees recognized only 18 percent of the abnormalities on average. After taking the course, these first-year fellows scored better than 45 percent — far higher than a control group of experienced fellows (with 23 months of traditional training), who scored 25 percent. After a refresher course six months later, the young trainees’ scores exceeded 77 percent.

“One of the questions is ‘Is this level of training better than the routine training?’” Fox said. “The NIH group has studied this, and the answer from a testing standpoint is a resounding yes. It is still an open question whether this truly improves patient care. But my feeling is that it does.”

Going forward, the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine plans to offer the Multi-institutional Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course annually. “The current plan is to have all fellows take it twice during their time at UAB,” Fox said. “I see it like a vaccine; you have the initial exposure, and then, after you have had time to absorb and apply it, you have the booster.”

Ventilators and AI

Abdul Tlimat, M.D.The Multi-institutional Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course at UAB is helping clinicians better respond to ventilator issues. In a separate project, Tlimat is developing another way to help.

Abdul Tlimat, M.D.The Multi-institutional Fundamentals of Mechanical Ventilation course at UAB is helping clinicians better respond to ventilator issues. In a separate project, Tlimat is developing another way to help.

Before he came to UAB, Tlimat completed a two-year postdoc in clinical artificial intelligence and machine learning at Harvard Medical School. He is the inventor of a software package called Vent Insights, which aims to leverage artificial intelligence to alert clinicians when ventilated patients are entering potentially hazardous dyssynchrony. The work is part of a prestigious NIH T-32 training grant he received.

With Vent Insights, “the goal is real-time clinical decision support that fits into two big buckets,” Tlimat said. “One is safety. Vent Insights is designed to be connected to all the ventilators in the MICU rooms and alert the physician if any safety parameters are exceeded.”

The second bucket is patient-ventilator dyssynchrony. Vent Insights is programmed to monitor patient-ventilator interactions and alert physicians when 10 percent or more of the waveforms in the previous hour have been abnormal. “That is the threshold that we think is clinically significant,” Tlimat said. The software then suggests several mitigation strategies. “I understand how busy a 14- to 16-bed ICU is,” Tlimat said. “This is a solution that can check in real time and alert the physician when something needs attention.”

Tlimat is now building the infrastructure to deliver this information to physicians in real time. His research is also gathering data to identify the exact threshold when dyssynchrony becomes harmful. “It is a very understudied area in general,” Tlimat said.

One of the reasons Tlimat chose UAB for his fellowship was the opportunity to work with top mentors like Surya Bhatt, M.D., professor and Endowed Professor of Airways Disease in the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine and director of the UAB Center for Lung Analytics and Imaging Research. Bhatt is now his research mentor. “When I interviewed here in my search for a pulmonary and critical care fellowship, I felt that the faculty understood who I am and what I wanted to do,” Tlimat said. “They said, ‘How can we get you to the next level?’ And then they made that happen.”