No two UAB classrooms are exactly alike. In this series, we take a deep dive into one course through the eyes of the instructor.

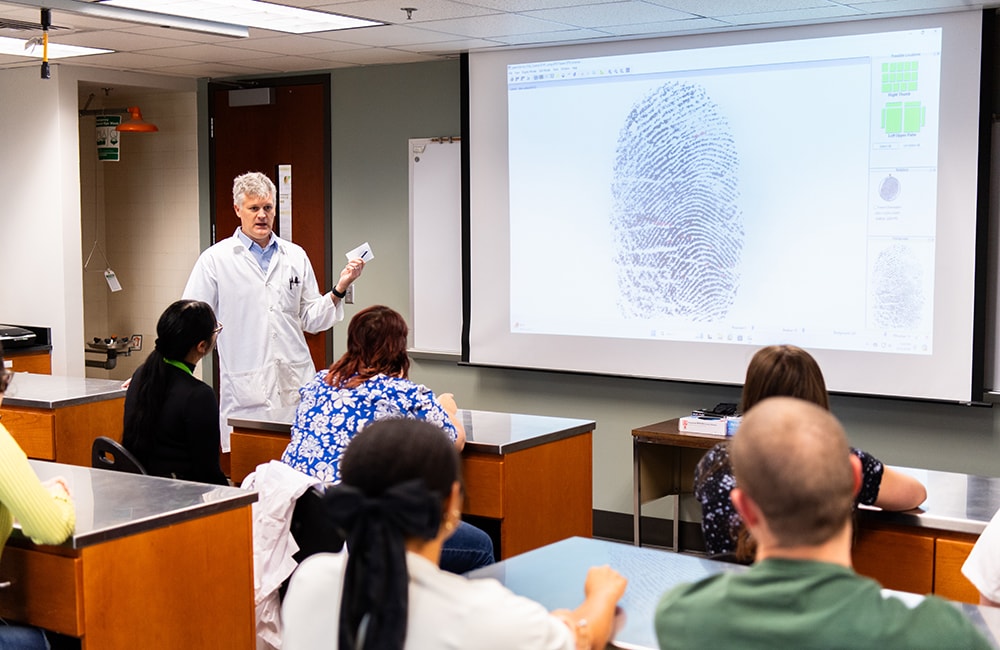

“CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” and “NCIS” are some of the most-watched television shows in human history. Inevitably, they are the reason many of the undergrads in the “Introduction to Criminalistics” and “Advanced Criminalistics” courses taught by Jason Linville, Ph.D., got interested in the science behind criminal investigations.

Linville, teaching associate professor in UAB’s J. Frank Barefield, Jr. Department of Criminal Justice, is also program director for the department’s Master of Science in Forensic Science program. He joined the faculty at UAB soon after “CSI” and “NCIS” launched — a year after he graduated from the university with his doctorate in biology in 2003.

“My original intent was to work in the field, but I started teaching and never left,” Linville said. “The relationships I build with the students are what have kept me in education. Getting to see them go out and graduate and start working in the field, that’s really the most rewarding part — combined with the fact that I could make that path a little easier, reduce their anxiety, help them understand how things work in a lab and how to get a job. I have taught many of the forensic scientists who now work in the state.”

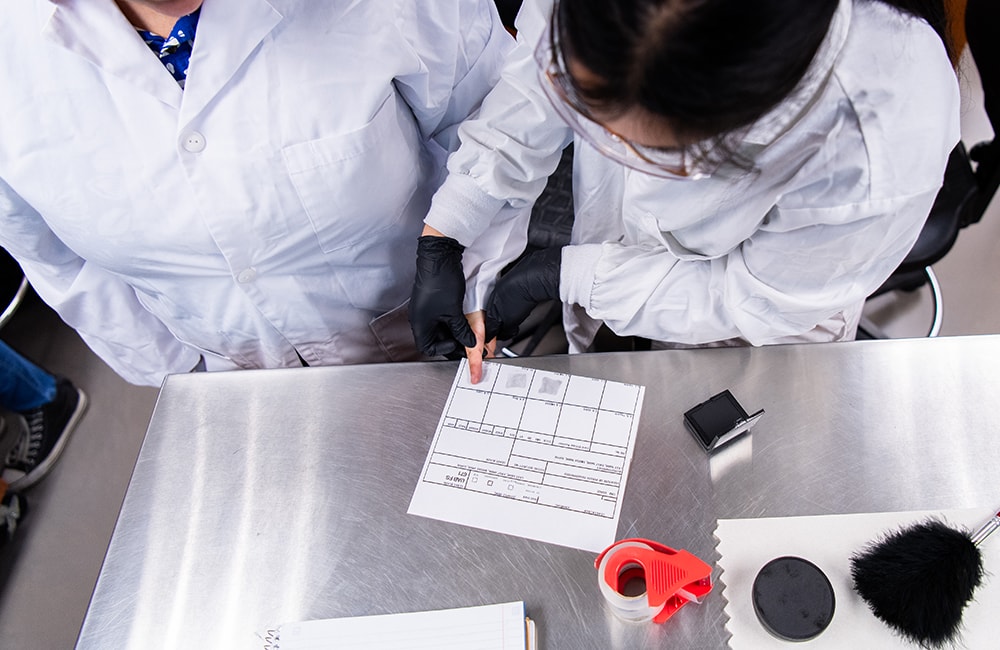

Students practice making inked fingerprints on paper. “So much fingerprinting now is done with a clear glass screen, but we do the ink print so they can see the difficulty of getting detail in a fingerprint,” Linville said. “A forensic scientist does not typically do that; it usually falls to someone in law enforcement or corrections. But we want them to be exposed to how the fingerprint is made.”

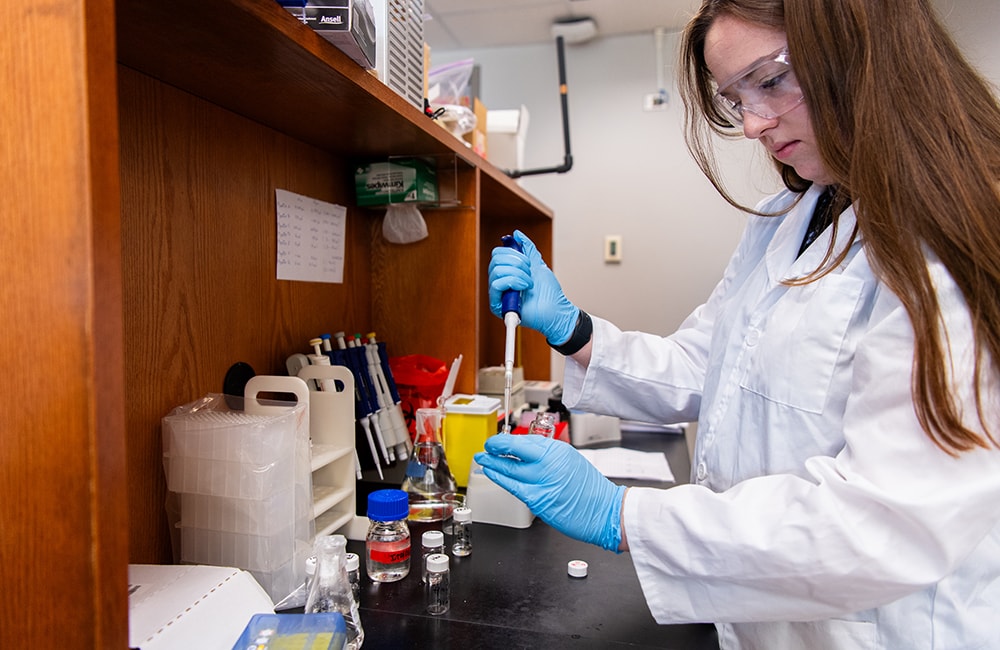

Students perform a TMB (Tetramethylbenzidine) test on a blood sample. The hemoglobin in blood reacts when it encounters hydrogen peroxide. “At the crime scene, law enforcement will collect a sample that appears to be blood, put it in an envelope and send it to the lab,” Linville said. “The first thing the forensic scientist will do, before the sample goes on to DNA testing, is perform the TMB color test. If you see a blue color, that goes into the case report: ‘Tested positive for TMB.’” (The blood is ordered from suppliers, although sometimes, when he wants a fresh sample, Linville will give himself a finger prick.)

A student in the drug-testing lab run by Linville’s colleague Professor Elizabeth Gardner, Ph.D., starts a drug preparation for testing. “Students quickly learn that, when you go into a lab to conduct work like drug analysis, the first step is getting your sample dissolved in liquid, and then the rest is pipetting it from one tube to another,” Linville said. As part of their coursework, students will be given small amounts of a substance in powder or pill form (often acetaminophen or another over-the-counter drug) and challenged to identify it.

Graduate students complete the final step in DNA analysis on one of the criminal justice department’s genetic analyzers. “DNA analysis is a three-step process,” Linville said. “First you extract the DNA from the biological evidence — the sample of blood or other bodily fluid. Then you take the extracted DNA, amplify it and measure the amplified DNA.” Genetic analyzers such as this capillary electrophoresis instrument are essentially measuring the length of a specific stretch of DNA bases, which varies in size from person to person. “The measurements that this analyzer produces are compared to the profile of your suspect,” Linville said.

In undergraduate courses, students analyze the genetic analysis data — often on samples of their own DNA. They also compare DNA extracted from a cheek swab sample with DNA extracted from a blood stain. “We create these scenarios where they are receiving mock evidence and they are responsible for discovering the origin of the sample,” Linville said.

At the graduate level, students will work through the entire process of DNA analysis for an entire 14-week course period, from receiving evidence to the final DNA analysis.

“Learning how to use the equipment and run the tests is not that complicated — but to be a forensic scientist, you need to be able to explain to the jury what is going on in each of the steps that you took,” Linville said. “You need to understand why it works and be able to explain that to others. You’re not just following a protocol; you need to be able to educate others. I enjoy being a part of that, helping students learn how to serve their community.”

To explore similar courses, visit the minor in Forensic Science program webpage on the J. Frank Barefield, Jr. Department of Criminal Justice website.