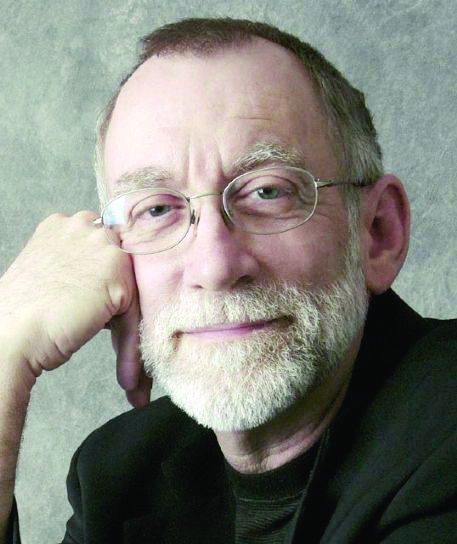

“I am delighted that Dr. Zehr has accepted this year’s Ireland Distinguished Visiting Scholar Award,” said Robert E. Palazzo, Ph.D., Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. “His work in restorative justice is seminal. Over the course of his career he has had an international impact, changing our perception of crime and violations. His work has shifted thinking from the older perception of crime as an act against the state to a more humanistic understanding of crime as a violation of the rights of individuals. His presence on campus will stimulate considerable discussion on the meaning of human rights and the importance of the civil rights movement in expanding our understanding of the concept of justice.”

“I am delighted that Dr. Zehr has accepted this year’s Ireland Distinguished Visiting Scholar Award,” said Robert E. Palazzo, Ph.D., Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. “His work in restorative justice is seminal. Over the course of his career he has had an international impact, changing our perception of crime and violations. His work has shifted thinking from the older perception of crime as an act against the state to a more humanistic understanding of crime as a violation of the rights of individuals. His presence on campus will stimulate considerable discussion on the meaning of human rights and the importance of the civil rights movement in expanding our understanding of the concept of justice.”Born and raised in the Midwest, Zehr studied at two Mennonite colleges before receiving a degree in European history in 1966 from the all-male, historically black Morehouse College in Atlanta, making him the first white person to graduate from the institution. He completed his Master of Arts degree in European history from the University of Chicago in 1967 and his doctorate in modern European history from Rutgers University in 1974. During and after his doctoral studies, he taught at the historic Talladega College in Alabama until he left in 1978 to begin practical work in the field of justice and victims’ rights. Since then, he has trained individuals working in the areas of restorative justice, judicial reform and victim-offender reconciliation in more than 25 countries and 35 states.

Zehr explains that restorative justice “is a relational view of wrongdoing and justice that focuses on addressing the harms, helping people to take responsibility for the harm they have caused, and seeks to engage those parties who have been impacted or have a stake in this.”

He made a major contribution to the field with the publication of “Changing Lenses: A New Focus for Crime and Justice,” widely seen as one of the first publications to articulate a theory of restorative justice. In it, Zehr explains that, in a justice framework based on punishment, crime is an offense against the state, whereas in a justice framework based on restitution and input from both victims and offenders, crime is viewed as a violation of people and relationships.

“In the book, I describe restorative justice as ‘an indistinct destination on a necessarily long and circuitous journey,’” Zehr said. “Now, several decades later, I can confidently say that, although it is still a journey with many curves, many detours and wrong turns, the road and its destination are not as indistinct as they once were. I believe that if we embark on this journey with respect and humility, and with an attitude of wonder, restorative justice can lead us toward the kind of world we want our children and grandchildren to inhabit.”

His Ireland lecture is entitled “After Selma: The Challenge of Human Rights and Justice.” Zehr explained that “the Selma march and the Voting Rights Act were huge milestones for human rights and justice, but they did not put issues of rights and justice to rest. [I want to] explore some of the challenges in defining and enforcing human rights in the 21st century, as well as ways that criminal justice has contributed

His Ireland lecture is entitled “After Selma: The Challenge of Human Rights and Justice.” Zehr explained that “the Selma march and the Voting Rights Act were huge milestones for human rights and justice, but they did not put issues of rights and justice to rest. [I want to] explore some of the challenges in defining and enforcing human rights in the 21st century, as well as ways that criminal justice has contributed to injustice.”

Zehr says that the lessons of Selma are still very relevant today, regardless of where human rights issues are occurring. “I teach in an international graduate program that brings together practitioners from all over the world to study and live together,” he said. “Many of them come from the front lines of human rights work—contexts where basic human rights are still in contention. They have often found that restorative justice re-orients how they approach human rights issues. They, in turn, have helped me to understand the importance of explicitly addressing human rights issues within restorative approaches.”

In addition to his influential work in restorative justice, Zehr also is an acclaimed photojournalist, a career that began as he documented the stories of the individuals with whom he worked. His photography publications include “A Dry Roof and a Cow—Dreams and Portraits of Our Neighbors,” “Doing Life: Reflections of Men and Women Serving Life Without Parole,” “Transcending—Reflections of Crime Victims, The Little Book of Contemplative Photography,” and “What Will Happen to Me?” about the children of prisoners. In 2013, he published “Pickups: A Love Story,” a collection of photos of pickup trucks and their owners.