UAB patient Katie Hooks uses her transformational story to spread awareness of scleroderma.

UAB patient Katie Hooks uses her transformational story to spread awareness of scleroderma.

(Photo provided by Brent Patterson)Katie Hooks, 23, was living a pretty normal life, until the morning she woke up with her face swollen shut. Soon after, she was on a ventilator at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, unable to speak or move.

Hooks’ journey to UAB Hospital began with what she thought was just an allergic reaction. She took some allergy medicine to try to mitigate the swelling of her face. But as the days went on, the swelling progressed to the rest of her body. She could not breathe, her body became stiff, and within months, she had completely lost her mobility and independence.

One night, Hooks woke up experiencing shortness of breath and was transported to UAB Hospital. She was quickly placed on a BPAP machine, a type of ventilator to help push air into her lungs and treat chronic conditions that affect breathing. Within hours, physicians at UAB diagnosed her with scleroderma and systemic lupus overlap with associated myositis.

Scleroderma is an autoimmune disease that causes the skin to become inflamed and swollen, often leading to hardening due to a buildup of scar tissue. Internal organs such as the heart, blood vessels, lungs, intestinal tract and kidneys can also be damaged. Lupus is an autoimmune disease that damages tissue in many parts of the body, including skin, joints, lungs and kidneys. Myositis, when it occurs in these disorders, causes muscles to become irritated and inflamed, eventually leading to the muscles breaking down and becoming weak.

“I really felt like I was slowly dying ...”

“By the time I was admitted to UAB, I had been struggling to breathe for months,” Hooks said. “I really felt like I was slowly dying, but I had convinced myself that I was overthinking this and that nothing was wrong. I just remember being admitted to UAB, closing my eyes and saying ‘God, if this is my time, please take me. I am ready to go.’”

Katie Hooks was living a pretty normal life, until she woke up one morning and noticed her face beginning to swell.

Katie Hooks was living a pretty normal life, until she woke up one morning and noticed her face beginning to swell.

(Photos provided by Katie Hooks)Four days later, as muscle weakness and lung inflammation set in, Hooks was placed on a ventilator. Although doctors cannot pinpoint the exact cause of this flare-up, they believe the stress on her body after having COVID-19 in August of 2020, combined with her heavy workload at the time, may have played a role.

“Everyone with an autoimmune disease has a genetic predisposition,” said Winn Chatham, M.D., associate division director for Clinical Services and director of Clinical Services for the UAB Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology. “For patients with autoimmune diseases, violent infections like COVID-19 can unmask the disease and cause a flare-up; but more often than not, we cannot specifically identify the triggering factor.”

Hooks was on the ventilator for the next three months. Scleroderma caused Hooks to have both systemic arterial and pulmonary arterial hypertension, which occurs when the arteries become damaged and narrowed. The hypertension damaged Hooks’ kidneys, causing her to go into kidney failure. While at UAB, doctors from multiple disciplines worked together to establish the best course of action to help her recover from this severe flare-up.

“Katie had a severe case that required input from multiple specialists,” Chatham said. “Health care providers from many of UAB’s subspecialty groups came together to attend to her care and help find a treatment plan that would allow for a smooth recovery.”

Hooks was prescribed immune-suppressing and chemotherapy drugs to help slow the severe lung and muscle inflammation. She was placed on dialysis for kidney failure. After three months of treatment, she was admitted to the Special Care Unit at UAB, where she began the process of being weaned off the ventilator. By the time she arrived to the SCU, she was completely immobile and needed 24/7 assistance.

Hooks’ journey to regaining her independence begins

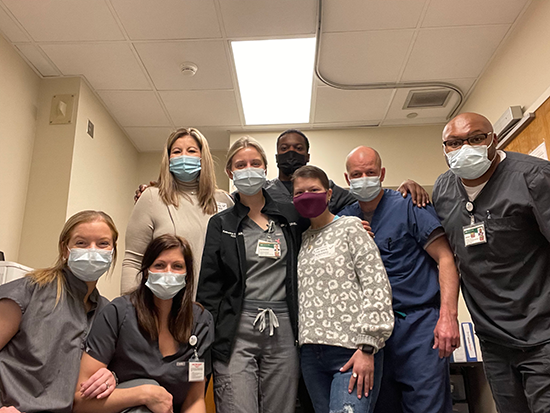

“I remember the day she came over to the SCU,” said Brent Patterson, Special Care Unit rehabilitation supervisor and one of Hooks’ physical therapists. “We were told about a college-age female who was critically ill. Katie’s case was not something we see very often. Her body had hardened to the point where she could not move anything. Everyone in our unit wanted to give her our all and see what happened.”

After a long road to recovery, Hooks’ life is returning to what it was before her flare-up. Her muscle strength, skin texture and joint flexibility have returned to normal, and she no longer requires supplemental oxygen. She will start respiratory school in the fall at Jacksonville State University with hopes to become a respiratory therapist at UAB one day.

After a long road to recovery, Hooks’ life is returning to what it was before her flare-up. Her muscle strength, skin texture and joint flexibility have returned to normal, and she no longer requires supplemental oxygen. She will start respiratory school in the fall at Jacksonville State University with hopes to become a respiratory therapist at UAB one day.

(Photo provided by Katie Hooks)When Hooks woke up, she was scared and depressed and did not fully understand what had happened to her. As the days went on, Hooks established trust with her care team and began making progress.

Initially, Hooks’ condition made it very difficult to identify the best positions to help her improve her mobility while protecting her skin’s integrity. Her respiratory team and physical therapy team worked with her providers to determine the best therapeutic interventions to help improve her mobility and ease flare-ups. They were eventually able to get her to sit up on the side of the bed — a significant accomplishment for Hooks.

Hooks’ mobility and her confidence continued to improve. The SCU staff held spa and hair days for her, and they would bring her clothes and shoes to motivate her. One pair of shoes, in particular, served as Hooks’ motivation throughout her stay at SCU.

“Katie has her eye on this one pair of tennis shoes and kept telling us that, once she left the SCU, she was going to get this pair of shoes,” said Jeff Hatcher-Fagan, a lead occupational therapist in the SCU. “The entire unit told her that, if she worked with rehab and continued with her routine, they would get her these shoes when she graduated, and when she graduated, that is exactly what we did. We focused on being there for her not only physically but spiritually as well.”

“Each step she took was like a leap of faith”

The day Hooks took her first step on her own was a transformational moment in Hooks’ journey in the SCU.

(Photo provided by Katie Hooks)“Each step she took was like a leap of faith,” Fagan said. “When she realized that she could take a step on her own, that is all it took to motivate her to push through the rest of her therapy. Through the Special Care Unit, we could collectively get together and cheer her on one step at a time. It’s all about crawling before you walk. She took a couple of steps forward and a couple of steps back; but in time, she was able to get better.”

(Photo provided by Katie Hooks)“Each step she took was like a leap of faith,” Fagan said. “When she realized that she could take a step on her own, that is all it took to motivate her to push through the rest of her therapy. Through the Special Care Unit, we could collectively get together and cheer her on one step at a time. It’s all about crawling before you walk. She took a couple of steps forward and a couple of steps back; but in time, she was able to get better.”

Through this experience, Hooks recognized her ability to do the things she wanted to do and decided to pursue a career in the medical field. After a long road to recovery, Hooks’ life is returning to what it was before her flare-up. Her muscle strength, skin texture and joint flexibility have returned to normal, and she no longer requires supplemental oxygen. She will start respiratory school in the fall at Jacksonville State University with hopes to become a respiratory therapist at UAB one day.

“I want to use my experience to help others in a similar situation,” Hooks said. “If I did not have the people in the SCU continuing to encourage me every day, I do not know where I would be today. I want to help those who may be going through a similar situation. One day, they can look back and see how far they made it, and all of the difficulty will be worth it.”

“One of the best parts about Katie’s recovery was not only seeing her regain her independence, but it was also finding out that, through her illness, she found her purpose and her way,” Patterson said. “One thing we wanted her to take from this experience is that she can use everything she has been through to lift others and be there for others like we were able to be there for her. She created a new chapter here. She learned how to reinvent herself through this process, and it was truly an honor to get to walk with her through her recovery.”