The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology is proud to announce the early success of its groundbreaking Anemia in Pregnancy Quality Improvement Initiative. This innovative program, launched in October 2023, has already made significant strides in reducing rates of pre-delivery anemia among obstetric patients, showcasing the power of evidence-based protocols in improving maternal outcomes.

The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology is proud to announce the early success of its groundbreaking Anemia in Pregnancy Quality Improvement Initiative. This innovative program, launched in October 2023, has already made significant strides in reducing rates of pre-delivery anemia among obstetric patients, showcasing the power of evidence-based protocols in improving maternal outcomes.

A new approach to screening and management

Anemia during pregnancy poses risks to both maternal and fetal health, including increased likelihood of preterm delivery, low birth weight, and the need for blood transfusions. In fact, the recent study, Optimal predelivery hemoglobin to reduce transfusion and adverse perinatal outcomes, published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology by UAB OB/GYN researchers showed that women with anemia (hemoglobin <10.6 mg/dL) were over five times more likely to require a blood transfusion during their delivery hospitalization than women who were not anemic.

The overwhelming majority of anemia in pregnancy is due to iron deficiency. Many women are iron deficient even before becoming pregnant, and the pregnancy further diminishes iron reserves over time. Once the iron stores are depleted, blood counts decrease, and patients become increasingly anemic.

Traditional management for iron deficiency in pregnancy has relied heavily on the standard recommendation for a daily prenatal vitamin, while targeted management was reserved until anemia developed or became severe. However, this is often not until late in pregnancy. Once diagnosed, anemia due to iron deficiency can take months to correct because the amount of iron that can be absorbed by the gut is limited. Even when iron is administered intravenously, it takes several weeks for the body to convert that iron into blood cells.

To address this challenge, the new UAB OB/GYN protocol incorporates a ferritin level test into routine prenatal labs at the beginning of pregnancy. Ferritin is a measure of total body iron stores, and its use allows for the diagnosis of iron deficiency even before it causes anemia. This addition allows for earlier detection and treatment of iron deficiency and individualization of care.

Once iron deficiency is diagnosed, the new protocol establishes a treatment plan depending on the severity and gestational age. Patients with severe anemia or those late in pregnancy are considered for prompt referral for IV iron infusion. Those with mild iron deficiencies or who are earlier in pregnancy generally receive dietary counseling and oral supplementation, and all patients are monitored throughout pregnancy for their response to treatment.

"By identifying and addressing iron deficiency earlier in pregnancy, we’re taking a proactive approach to preventing and treating maternal anemia," said Carolyn Webster, M.D., assistant professor for the UAB Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. “Our new protocol also supports individualized counseling and management based on each patient’s specific ferritin and hemoglobin levels. This type of personalized care helps patients feel more engaged and invested in their treatment plan.”

Evidence-based innovation

Webster’s passion for addressing maternal anemia traces back to her fellowship years when she first encountered the challenges of iron deficiency in pregnancy. She saw firsthand how difficult it was to make small but meaningful changes when it came to treating anemia. Despite the well-known importance of iron in pregnancy, the standard approach—oral supplementation—was often slow, poorly tolerated, and ineffective for many patients. By the time anemia was detected, it was often severe and difficult to treat quickly, putting both mother and baby at higher risk.

Webster’s passion for addressing maternal anemia traces back to her fellowship years when she first encountered the challenges of iron deficiency in pregnancy. She saw firsthand how difficult it was to make small but meaningful changes when it came to treating anemia. Despite the well-known importance of iron in pregnancy, the standard approach—oral supplementation—was often slow, poorly tolerated, and ineffective for many patients. By the time anemia was detected, it was often severe and difficult to treat quickly, putting both mother and baby at higher risk.

Webster was particularly struck by the data coming out of UAB OB/GYN, which highlighted the alarming prevalence of anemia among 18,000 pregnancies at UAB. The numbers were staggering; even mild anemia increased the likelihood of requiring a blood transfusion fivefold. Women who entered pregnancy already anemic faced even higher risks, including postpartum complications and longer recovery times.

Recognizing an opportunity for improvement, a multidisciplinary team of UAB clinicians was formed, including physicians from Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Women’s Reproductive Healthcare, and Hematology. The team developed the new protocol, which in addition to earlier detection of iron deficiency, also incorporates IV iron infusions. IV iron, which corrects iron levels much more rapidly than oral supplements, is not a new concept in the treatment of iron deficiency. However, it has not been well established which patients benefit from this therapy in pregnancy. Webster and her team worked on refining scheduling protocols to optimize the delivery of IV iron treatments, ensuring that women who needed intervention could receive it efficiently. Early results were promising—using data to guide implementation, she saw how quickly anemia rates improved.

Remarkable results in just six months

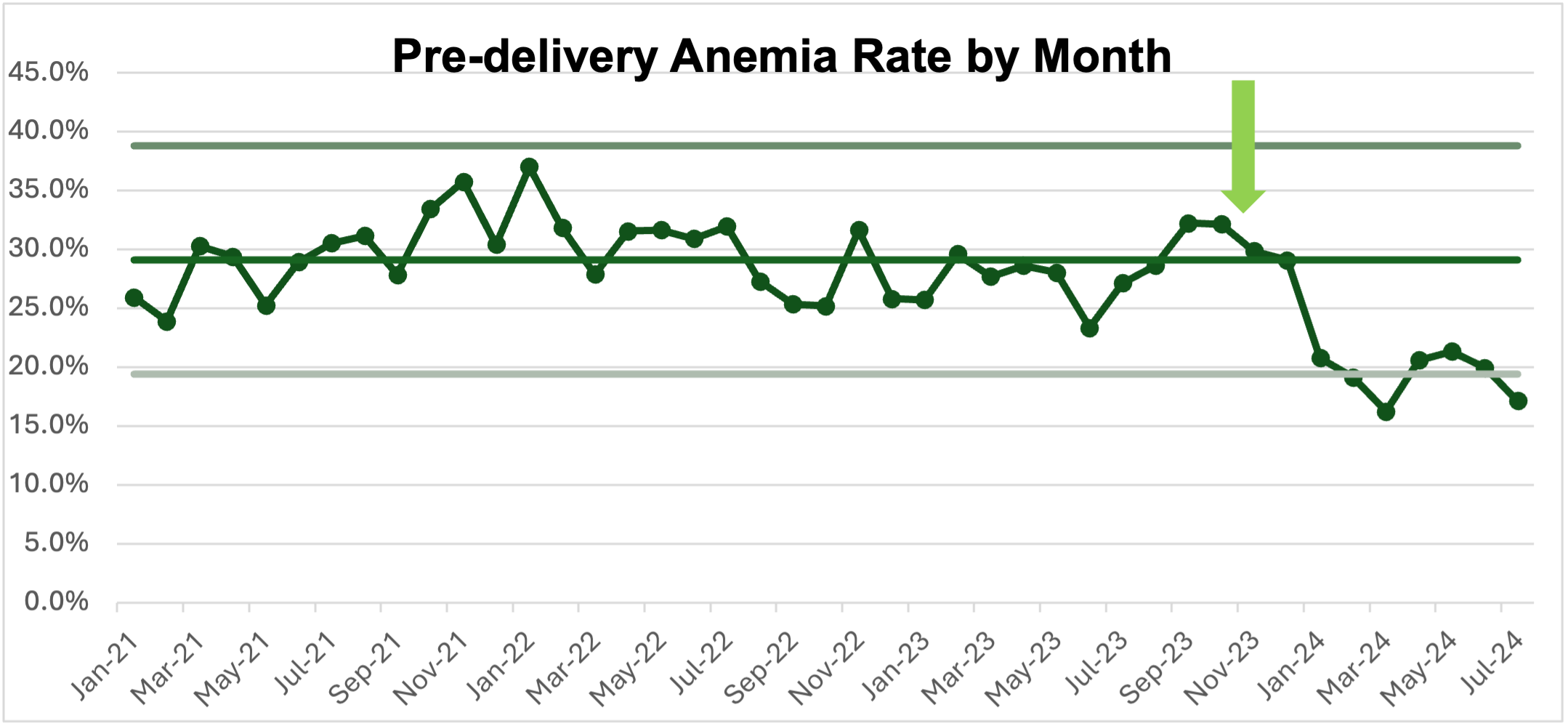

The impact of the initiative has been striking. Prior to the protocol, 29% of patients were anemic at the time they were admitted for the birth of their infant (hemoglobin <10.6 mg/dL). In just six months post-implementation, that rate dropped to 19%, a statistically significant decrease (p<0.001). Rates of moderate-to-severe anemia (hemoglobin <9.0 mg/dL), for whom transfusion risk is the highest, dropped by over half, from 5.4% to 2.4% (p<0.001).

The impact of the initiative has been striking. Prior to the protocol, 29% of patients were anemic at the time they were admitted for the birth of their infant (hemoglobin <10.6 mg/dL). In just six months post-implementation, that rate dropped to 19%, a statistically significant decrease (p<0.001). Rates of moderate-to-severe anemia (hemoglobin <9.0 mg/dL), for whom transfusion risk is the highest, dropped by over half, from 5.4% to 2.4% (p<0.001).

The initiative's effectiveness is also highlighted by its rapid implementation within a large healthcare system. Before October 2023, only 9% of obstetric patients had ferritin levels drawn during pregnancy. This number has since soared to 80.5%, demonstrating strong adherence to the new protocol.

Safety monitoring and ongoing improvements

To ensure patient safety, UAB OB/GYN has closely monitored infusion reactions associated with iron treatments. Between January and June 2024, the infusion reaction rate was 10%, with all cases classified as mild or involving isolated symptoms, such as facial flushing, back or joint pain, or itching. Notably, there were no instances of anaphylaxis.

"Safety is a top priority when implementing any new treatment protocol," emphasized Webster. "While we’ve seen excellent results, we’re remaining vigilant to ensure that our new treatment strategy is not just effective but also remains safe."

Looking ahead

The early success of the initiative begs a critical question: Should this approach become the standard protocol for all pregnant patients? The evidence strongly suggests it could be a game-changer in reducing maternal anemia. However, to cement its place in clinical practice, it is essential to demonstrate not only that it works but that it leads to measurable improvements in maternal outcomes.

“This initiative is grounded in evidence and has shown promising preliminary results, but we’re committed to ensuring that the final outcomes reflect our intended goals,” said Webster. “Treating iron deficiency shouldn’t be just improving a number. We want to make sure it improves health.”

The initiative's next phase will focus on tracking blood transfusion rates. The goal is to determine whether using this protocol to reduce pre-delivery anemia leads to fewer blood transfusions, further improving maternal health outcomes.

A bright future for maternal health

UAB’s Anemia in Pregnancy Quality Improvement Initiative exemplifies how targeted, evidence-based changes can impact maternal health. As the program continues to evolve, it offers hope for reducing anemia-related complications and improving outcomes for mothers and babies across Alabama and beyond.

More than simply creating an algorithm for treating anemia, Webster wants to empower patients with knowledge. She believes women should understand the importance of iron in pregnancy, their own ferritin levels, the best ways to replenish iron stores, and how to manage side effects they might encounter, such as constipation and nausea, so they can make informed choices about early prevention. After all, growing a baby takes about a full gram of iron, and deficiencies can escalate into serious complications without proactive management.

Webster’s initiative is not just about treating anemia—it’s about transforming the way pregnancy care is approached, ensuring that every mother has access to the best possible prevention and treatment strategies.

As Webster summarized it, “Every patient deserves the best we have to offer, even when it comes to something as simple as iron.”