“Wheels are up,” declared the captain of the aircraft carrying Sheldon Kushner, M.D., and other military personnel departing from Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon, Vietnam—ending Kushner’s arduous tour of duty as a trauma surgeon during the height of the Vietnam conflict in 1969. Kushner, a native of Montgomery, Alabama, recalls the captain’s words unleashing a flood of emotions. “The sense of relief and joy was overwhelming. I was homebound for Travis Air Force Base in California and on to Birmingham to see my family.”

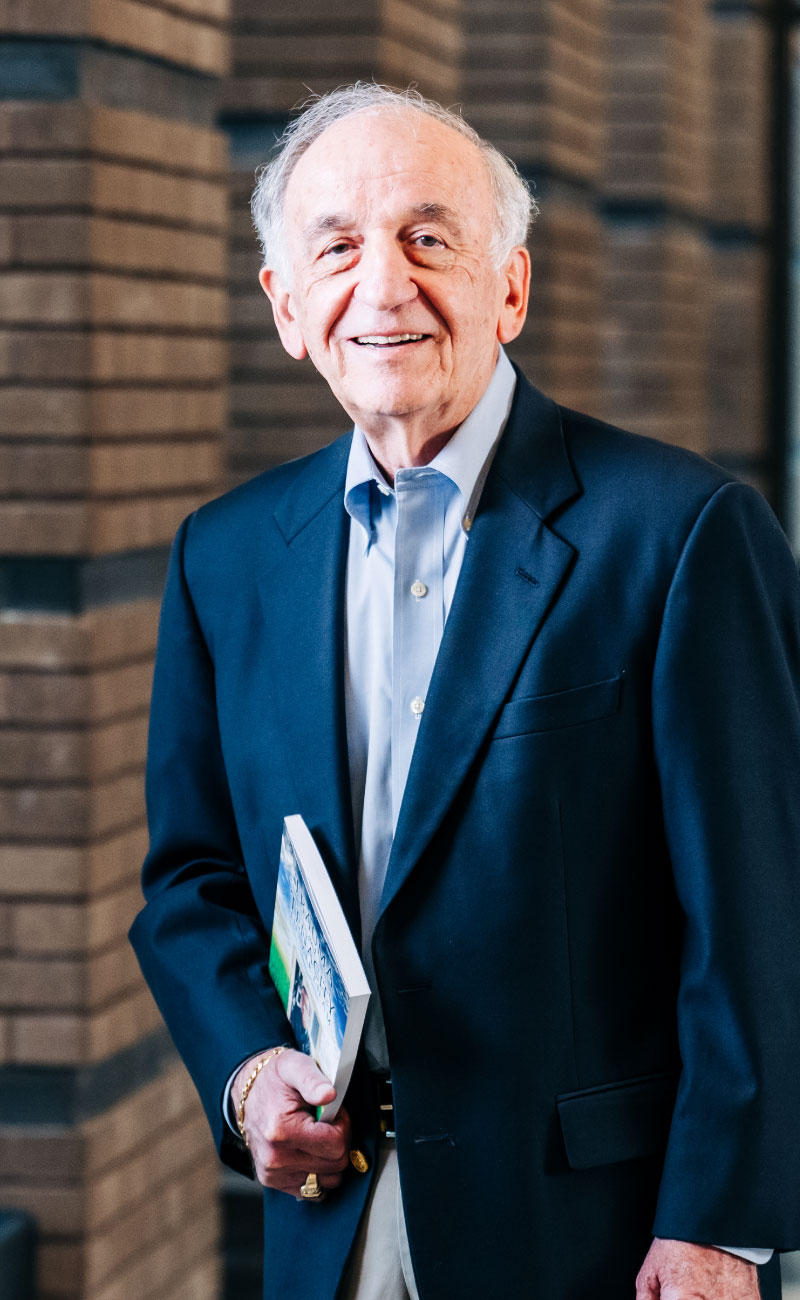

Sheldon Kushner, M.D.A 1966 graduate of the University of Alabama School of Medicine (now the Heersink School of Medicine), Kushner arrived in Vinh Long in the Mekong Delta, southwest of the former city of Saigon, as an Air Force Captain in early 1968, soon after the Tet Offensive in which the Vietcong and North Vietnamese forces launched intense, coordinated attacks that put civilians in the crossfire. Kushner assisted a team of doctors at a Vietnamese civilian hospital as part of the U.S. Military Provincial Health Assistance Program that provided medical aid for civilian war casualties. “I was assigned to perform trauma surgeries, although I didn’t have the training to do it and wasn’t prepared,” said Kushner, who at 26, had completed medical school and a one-year internship. “It was on-the-job training.”

Sheldon Kushner, M.D.A 1966 graduate of the University of Alabama School of Medicine (now the Heersink School of Medicine), Kushner arrived in Vinh Long in the Mekong Delta, southwest of the former city of Saigon, as an Air Force Captain in early 1968, soon after the Tet Offensive in which the Vietcong and North Vietnamese forces launched intense, coordinated attacks that put civilians in the crossfire. Kushner assisted a team of doctors at a Vietnamese civilian hospital as part of the U.S. Military Provincial Health Assistance Program that provided medical aid for civilian war casualties. “I was assigned to perform trauma surgeries, although I didn’t have the training to do it and wasn’t prepared,” said Kushner, who at 26, had completed medical school and a one-year internship. “It was on-the-job training.”

The work was exhausting and grueling, with Kushner and another young physician performing up to six major operations a day in two separate operating rooms, including limb amputations from land mine explosions and open abdominal surgeries to remove shrapnel and repair major blood vessels. All were civilian injuries that could have been caused by any side in the conflict. “There was such a high volume of cases, we worked 13- and 14-hour days and could never catch up,” Kushner recalled.

Kushner and his colleagues stayed in an old French hotel, acquired by the U.S. Army, with a group of Army Rangers, Navy SEALs, Navy Seabees, and civilian nurses, totaling 120 people. “It wasn’t safe to be at the hospital at night because that’s when the Vietcong launched most of their attacks,” said Kushner, a retired obstetrician and gynecologist (OB/GYN) who now lives in Point Clear, Alabama. He vividly remembers the terrifying, nighttime sound of North Vietnamese rockets exploding in surrounding villages—a sign that high numbers of civilian casualties would be flooding the hospital at daybreak.

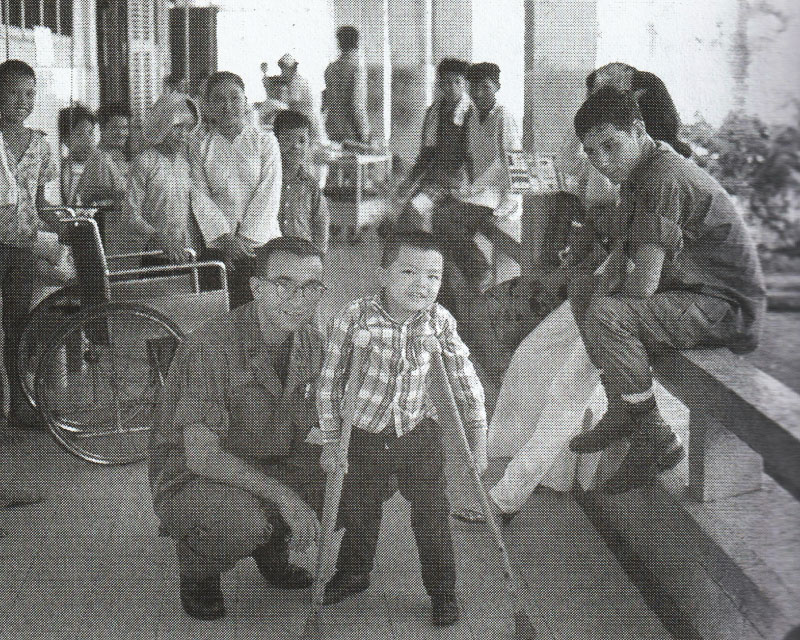

“Up to 25 severely injured civilians were waiting to be treated each morning,” he said. “I’ll never forget the day a huge truckload of children arrived from a school that was hit by a rocket.” Kushner also has heartrending memories of a six-year-old boy named Loc whose injuries from stepping on a land mine required Kushner to perform a life-saving amputation of the boy’s legs below the knee. “The Seabees made him a wheelchair, and we found some artificial legs,” said Kushner, who recalled teaching Loc some English and reading him stories when his grandmother brought him to visit at the hospital. “I felt horrible having to leave him when my tour was over,” Kushner said. “I’ve tried to find him a few times but was unsuccessful.”

Kushner said that while the profound fatigue was something he has never since experienced, the challenge of performing major surgeries without proper training was unimaginably stressful. “I’d sometimes perform surgeries with the medic holding Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy turned to a page I needed to see,” he said. Kushner recalls that his excellent medical school training was crucial, adding, “I had the good fortune to be taught and trained in Birmingham by some of the best physicians and surgeons in the country.”

Kushner corresponded regularly with surgery faculty member Holt McDowell, M.D., and occasionally with surgery resident Robert Yoder, M.D., requesting guidance for specific operations. “They faithfully responded with detailed instructions in letters and audiotapes,” he said, adding that his experience in Vietnam positively impacted how he later practiced medicine. “I learned not to panic when I saw something bad—to stay calm and stay with it. I developed confidence in myself from that experience.”

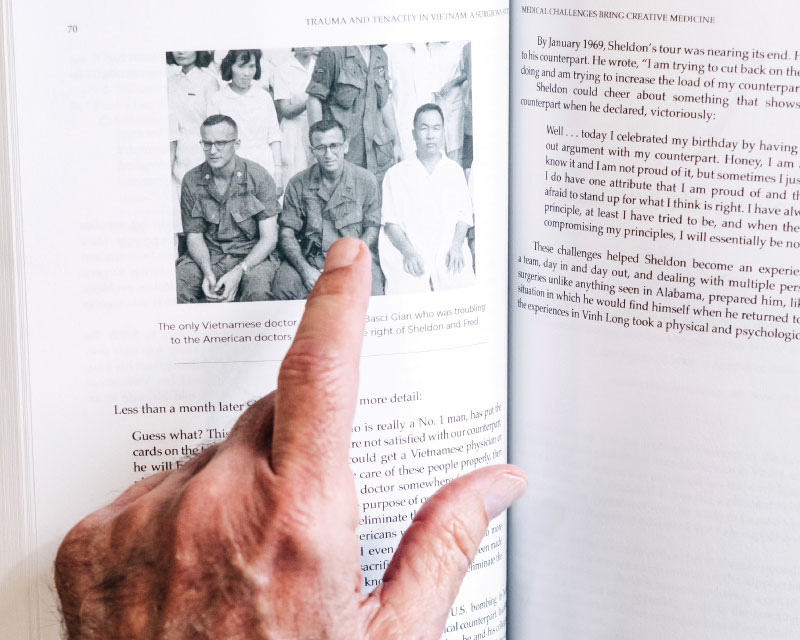

Kushner left the service in 1969 and completed residency training in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Cincinnati, choosing a specialty that he described as “different and a bit happier.” After a few years of private practice, he taught in an OB/GYN residency in Pensacola, Florida. In 1991, he went back into private practice in Vero Beach, Florida, where he spent the greater part of his practice career. A 2017 book by author Mary Jane Ingui, Ph.D., "Trauma and Tenacity in Vietnam: A Surgeon’s Story," details Kushner’s experience based on more than 300 letters he wrote to his wife from Vietnam.

“People think the war is over when you come home, but it never leaves you,” Kushner reflected. He said while Vietnam is a war most people never understood, he knows that he and his colleagues had a noble purpose and made a difference in the lives of the civilians they treated. “A part of war that is often not considered is the devastating toll on civilian lives,” he said. “I left Vietnam with a deep sense of pride for our work at that hospital in Vinh Long and tremendous respect for our brave, patriotic young men fighting in that terrible war.”

A hospital-based program to train and deliver sophisticated care was called Military Provincial Health Assistance Program (MILPHAP). Kushner was part of the MILPHAP team in Vihn Long, Vietnam.

A hospital-based program to train and deliver sophisticated care was called Military Provincial Health Assistance Program (MILPHAP). Kushner was part of the MILPHAP team in Vihn Long, Vietnam. Kushner and fellow surgeons at the Vinh Long Hospital.

Kushner and fellow surgeons at the Vinh Long Hospital. Six-year-old Loc, whose injuries from stepping on a land mine required amputation. Kushner found artificial legs for Loc.

Six-year-old Loc, whose injuries from stepping on a land mine required amputation. Kushner found artificial legs for Loc.